Condors and Wind Turbines: Green-vs-Green Conflict Revisited February 29, 2012

Posted by Michael Hoexter in Energy Policy, Renewable Energy, Sustainable Thinking.5 comments

(This post was originally published at Renewable Energy Magazine)

The likely conflict between the extension of the California condor’s habitat and wind development in California pulls the green movement in opposite directions, an unfortunate story that has repeated itself a number of times in the combined environmental-climate action community in the United States. Both sides of the conflict have personal relevance to me: I remember as a child reading about and cheering on the condor, in part because of its role as the largest flying bird in North America, as well as its endangered status. More recently, I have also advocated for the last 5 years that worldwide we build a Renewable Electron Economy, a massive build-out of wind and solar energy in the context of a multi-technology, largely renewable energy powered electric grid.

In his excellent article in Forbes, Todd Woody summarizes the conflict between wind turbines and the reintroduced condor and explores some of the technological fixes that are being explored by scientists and the wind industry. The condor had been decimated via poaching, DDT poisoning and lead poisoning from swallowing bullets in the carrion that this quite intelligent vulture prefers to eat. Via what some say is the largest species conservation effort in North America, wildlife biologists and conservationists have worked hard to revive the condor by running nurseries with the few remaining birds and then, since 1992, releasing some back into the wild.

Such is the success of the efforts to revive this critically endangered species that approximately 400 condors are now active in a larger portion of their native range throughout the mountains of Californiaand the Western US. Apparently condors fly in thermal updrafts near mountain ranges and at an altitude which puts them potentially on a collision course with the blades of wind turbines in areas such as the Tehachapi Mountains of Central-Southern California. If a condor were killed, the owners of the project might face criminal prosecution. While there have yet been no documented deaths of condors from collision with a wind turbine, a number of large scale projects have been cancelled because of fears of such an event occurring. Wind project developers are aware of and attempting to avoid projects that have the highest likelihood to kill a condor but to many wildlife conservationists and fish and wildlife authorities, almost any project in this wind-rich area of Californiais too much risk. A 2005 US Forest Service study determined that overall wind turbines contribute to a small fraction of human-caused bird deaths of all species with buildings killing 4 orders of magnitude more birds than wind turbines.

One possible technical solution, discussed in the Forbes piece, is to develop a system of condor detection plus wind turbine controls that enable stoppage of turbines when condors approach them. These technologies have not matured to the point where they could be used in projects that are already in California’s approval process.

The wind turbine-condor conflict is the latest in a series of setbacks for large-scale renewable development on California’s renewable-energy rich landscape. Concerns about impacts on the desert tortoise and Mojave ground squirrel have scuttled a number of large-scale solar projects in California’s deserts. California is attempting to meet a fairly ambitious renewable portfolio standard of 33% of electricity generated by renewable energy by 2020, which is now in doubt given the roadblocks put up by issues related to wildlife and viewscape conservation.

We are starting to see an emerging pattern of “green-on-green” political and ethical conflict surrounding what are the acceptable costs and speed with which renewable energy generation should be built. While the condor vs. turbine conflict has some unique features, it corresponds to a now common “map” of the positions available to those who believe themselves to be preserving natural habitats, wild species and/or the habitability of the globe more generally. Some of these positions are compatible with one another and are found within the same group or pro-or-con argument; others are diametrically opposed to each other:

- Return to Nature – Ever since the Romantic reaction to industrialization in the early 19th Century, there have been individuals and groups that believe that human civilization should retreat before and should come more under the influence of eco-systems that are not controlled by people (i.e. Nature). While this is not an official or stated position of any mainstream environmental organization, some individual environmentalists and or defenders of wildlife might feel that human civilization must retreat to create a more bucolic world. From a slightly different angle, some “neo-Malthusians” might join in the belief that population growth and the ecological footprint of humanity has become too great, thereby necessitating a contraction of human societies. At its most radical this stance can become a celebration of the collapse of manmade structures and society in the face of non-human dominated eco-systems. Hollywood has provided us with some visions of this future in movies like “Planet of the Apes” and “I am Legend”. The condor’s advance into some of its previous range opens up the possibility that human intentions to build or maintain the civilization’s footprint could be abandoned in the face of strong wildlife preservation concerns.

- Wildlife/Habitat Preservationism – Most who are strongly committed to protecting wildlife over and above other concerns believe that, while they may be motivated by dreams of a significantly “wilder” landscape, the highest good is to protect existing remnants of endangered species and their habitats. This stance is commonly held in mainstream environmental organizations, such as the Sierra Club or the Nature Conservancy, as well as their base among generally politically left-of-center member/contributors. Additionally various governmental bureaucracies such as parts of the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the Parks Service represent preservationist interests, especially those which are tasked to preserve land areas or wild species.

- Anti Wind-Turbine Activism – Wind turbines are the targets of activists who focus on a number of real or perceived attributes of the technology without offering a clean energy alternative. Besides concerns about threats to birdlife, these activists focus on the visual appearance of the turbines, the perceptible or imperceptible sound they make, and, less commonly, the intermittency of power produced by the turbines. These activists usually do not count themselves as environmentalists or “green”.

- Brownfield/Rooftop PV Only – A compatible position with wildlife preservationism is the idea that renewable energy development should be confined to only so-called “brownfields” where there is already human development or rooftop installations. This is sometimes called “distributed energy”, though the definition of “distributed” varies depending on who is using the term. This position focuses on reducing the external and often visible impacts of energy development but tends to ignore the parameters of replacing fossil energy supply as it is currently used to power civilization. Often this group combines this energy prescription with a political preference for small-scale, local political and economic organization, a.k.a. “small is beautiful”.

- “Green is Good” – A position that is common among politicians and that is fairly widely held in the population is that “green is good” in some undifferentiated way. Many people don’t bother to read up on or feel themselves to be competent to judge the merits of various green issues. On the other hand, they want to think of themselves as generally virtuous people who do not support the clubbing of baby seals or who try to recycle when it is made easy. The opinions of this group will be influenced by those with stronger views for, and against, any particular green issue.

- Anti-AGW, Pro-RE (AGW= anthropogenic global warming: RE = renewable energy) – Supporting a wide-range of RE powered generators to replace fossil fuels for electricity production and transport, this position shared by some climate activists, business groups, and renewable energy advocates focuses on climate impacts of current fossil fueled transport and electricity generation. Parts of mainstream non-profit environmental organizations have supported this position, including Greenpeace and the Sierra Club. Unlike the “small is beautiful” distributed RE position, these groups see a role for large scale renewable development and a renewable energy “supergrid” to balance energy flows on the electric grid. Some who support this position specifically argue against nuclear power while others accept that nuclear power will play some role in climate strategy. I count this position as my own but do not justify my views via total opposition to nuclear power. The conflict between condors and wind development is a challenge for this group, as many in it consider themselves to be as “green” as anybody else.

- Anti-AGW, Pro-Nuke – A number of advocacy groups, business interests, and governmental officials argue for nuclear power, justifying their views via the predictability of the power generated by nuclear plants and using, in my opinion, optimistic projections about its near term development and safety. Most in this camp argue for nuclear power against renewable energy, often making pessimistic or negative statements about the technical or environmental attributes of RE electrical generation technologies such as wind turbines. There are some in this camp that see renewable energy and nuclear power as complementary as witnessed by the French national energy strategy which combines both nuclear and renewable energy. Some with these views emphasize the high level of energy demand and often de-emphasize or criticize energy efficiency efforts. There are a number of active Internet “trolls” that write from this position with varying degrees of interest in combating climate change but always taking jabs at various perceived and real drawbacks of renewable energy, including potential conflicts between wind turbines and birds. The Fukushima disaster has put a damper on enthusiasm for this position for the time being.

- Innovation First – Optimism and cheerleading for technology in a more general sense can be found among a substantial group that see in technological innovation a solution to almost all energy problems. The sole role for political decision makers in this view of the world is to foster innovation and the technical skills associated with continual innovation. As an example, the Breakthrough Institute hopes to accelerate “breakthroughs” or quantum leaps in innovation as a means to solve energy problems. The political love of innovation is however more generalized and is, in the United States, at least, almost a secular religion. Innovations in wind turbine technology and bird detection would be seen as the solution rather than political conflict over the role and valuation of different aspects of the dependence of people on the environment (energy use vs. individual species preservation).

- More Energy is Better – Finally there is another position that is compatible with the corporate goals of diversified energy companies (including some large fossil fuel conglomerates) and technology-neutral investors, which sees in the building of more energy supply of almost any kind an unalloyed good. This position would support the building of wind turbines (or any other energy production facilities) and might then lobby to get certain projects built, given an opportunity for an acceptable return on investment. Those with this position do not tend to support restrictive policies on energy development but also will work with and lobby regulators or government officials if regulation allows their business to continue or grow.

- Anti-Enviromentalist, Climate Denial – In the background and currently a very politically powerful position in the US is right-wing anti-environmentalism that also denies the reality of climate change. While it is not clear which “side” of the condors vs. wind turbines debate people with this position would support, it is more than likely that supporters of this position would want to encourage the division between supporters of wildlife protection and supporters of renewable energy development. It is my belief that many with this position would show a preference for wildlife protection over the systemic changes implied in active efforts at climate change mitigation.

The diversity of these positions, most of which might call themselves “green” or green affiliated in some form or other, shows how easily divided environmentally interested political forces are in theUnited States and perhaps beyond.

At the end of this list are the powerful opponents to both renewable energy and to wildlife conservation: the radicalized right-wing in America, for the most part in the Republican Party, corporate groups opposed to changing the energy system, and, in particular, the fossil fuel lobbies. The inter-green conflicts give these anti-environmental groups enormous leverage to stall and divide action on topics of mutual interest to make America“greener” in some form or other.

To some, who hold one or more of these views, this issue is already a settled matter in terms of technical and political choices. For instance, those who believe that energy should only be generated locally at a small scale, believe that the solutions are already there for a habitable civilization to be powered by PV, lead acid batteries, energy efficiency, and perhaps local biomass burning. Thus a conflict with wildlife preservation would, they imagine, be avoided. I am not convinced that the distributed-PV-only vision would work on a technical level, nor do I believe that local is necessarily better: I have not yet seen a realistic scenario for the production, maintenance and disposal of the millions of tons of batteries required to store energy for a populations of 100’s of millions and billions of people. Nuclear advocates, likewise, think that nuclear power’s drawbacks will be quickly overcome by technological advances, thereby making the conflict between wind power and birds moot.

Many in the environmental community are not even producing what they believe to be a realistic systemic solution but are simply committed to an issue, which they consider to be irreproachable in terms of its morality. Sometimes implied in these issue by issue commitments is a deeply held vision of a more (non-human) nature-dominated world and the interests of the human community as a whole and calculations of its energy requirements more or less “be damned”.

Each of these positions makes assumptions about the world, about human beings and about technologies that need to be clarified in order for a rational discussion to take place about how to proceed here in California and elsewhere. These assumptions are part of what might be called a “decision space”. In coming posts, I will develop a map of the underlying decision space within which these conflicts take place.

An “All of the Above” Energy Policy Concedes the Future June 10, 2011

Posted by Michael Hoexter in Climate Policy, Efficiency/Conservation, Energy Policy, Green Transport, Renewable Energy.3 comments

The dominant theme in President Obama’s 2011 State of the Union address was “winning the future”. As has become typical during Obama’s tenure in office, the speech and the metaphor selected seemed designed to avoid making a clear and decisive statement and to make peace with his Republican opponents. However if we take the President’s metaphor seriously, Obama’s energy policies seem more likely to continue conceding the future to other nations who are making real choices in the area of energy. Rather than take the initiative as he could as President, Obama has chosen in energy to make friends with almost every aspect of the energy industry, green and, in particular, brown.

Choosing “All of the Above”

The 2008 Energy flow diagram for the US (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory) shows the dominance of fossil energy (bottom three flows) in the US energy use system. A transformation of this energy flow diagram towards sustainable sources of energy will be impossible without aggressive federal government policy

While I had hopes that President Obama would significantly change our approach to energy in favor of sustainable energy choices, as it turns out the best description for his approach would be that it is an “all of the above” energy policy. Not as aggressively retrograde as his predecessor, George W. Bush, Obama has tried to show that he is not only a reliable friend to the oil and gas lobbies but also is willing to “throw a bone to” the renewable energy industry and public transit supporters. He has made a cautious foray into high speed rail though not bold enough to insure that HSR has a secure funding base. His administration provided loan guarantees to large renewable energy projects that were already in the pipelines. He seems to treat energy and transport alternatives as, for the most part being representative of a larger political “constituency” which he courts by offering more or less support for their presumed favorite projects or ideas.

The problem with the apparent equivalence in this political strategy is that it ignores the real-world physical energy balance, the depletion curve of fossil energy, and emissions of US society as well as political and market power differences between these constituencies and industry segments. Oil, gas and coal companies are the dominant energy companies on the planet and have considerable power in Washington as well as beyond the Beltway in the real economy. In order for there to be actual equality between these different groups, if that is even a desirable outcome, government institutions would need to favor the “infant industries” of renewable energy and energy efficiency to compensate for years of subsidy and centuries of precedence in the energy and transport sectors for fossil energy. Our society has to an overwhelming degree been built around oil, gas and coal.

Another approach, that is not even on the table, would be, rather than play to one or the other constituency, to build an energy policy based on the real geological, geopolitical, environmental, and social factors that condition energy availability and energy use. Such a policy would favor renewable energy and energy efficiency but would also challenge these segments to radically scale up production and reduce emissions sooner rather than later. Furthermore only government policy can push the now not-inexpensive energies of the future down the cost curve.

Beyond trying to project the image of not playing favorites between industry segments, Obama seems to view energy very much in “Left-Right” terms. The 2009 stimulus package had some promising financing for renewable energy projects (optically “Left”) but these have not so far turned into a durable renewable energy support policy beyond the existing status quo. In March 2010, Obama announced plans to open new areas to offshore drilling, clearly an effort to blunt the “drill baby drill” mantra of the Republicans (optically “Right”). Natural gas drilling and fracking continues with the addition of a new drilling safety panel which seems to be an effort to address pro- and anti-fracking lobbies. Energy efficiency, the no-brainer energy solution, has been given some support but is not highlighted. An ultra-low energy retrofit of the White House, for instance, is inconceivable within Obama’s current political strategy because it would seem too “Left”, too hippy-ish.

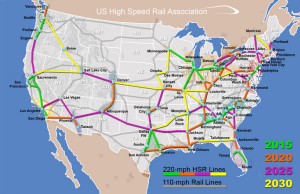

The US High Speed Rail Association projects that its 2030 vision linking most US states by 200 mph high speed rail links would cost $600 Billion dollars. These rail lines would serve "Red" and "Blue" states alike. The relatively cautious approach of the Obama Administration focusing on a few projects does not communicate the potential of high speed and electric rail more generally: it functions as insulation against oil shocks in a nation extremely vulnerable to the price and availability of oil.

Of a piece with this picture is the level and type of support offered to, for instance, high speed rail projects. Obama “slipped in” $8 billion dollars for 11 high speed rail projects but which in itself would not buy a single high speed rail route on its own. While this was the single largest investment in high speed rail in the US, it pales in comparison with investments made by China,France or Spain in HSR or, for that matter, the comprehensive vision of the US High Speed Rail Association.

The lack of “bigness” in Obama’s support made it, I believe, much easier to attack from the Right. Not as many constituencies could be served by the smaller package to be divided between 11 projects. But more damaging, was the lack of a comprehensible vision for the American people about what HSR was about, as a sustainable alternative to regional air travel throughout the US. If Obama had presented a multi-year plan to fund any the USHSRA’s 2020 or 2030 vision, he might have had to fight more with Republicans but at the same time, there would be a greater understanding of the utility of having an HSR network rather than single lines that serve fewer constituencies. In an effort to avoid conflict, the point of the entire effort was not so easy to communicate and win political points or inspire hope.

In energy efficiency and energy conservation, which are together possibly the greenest energy measures, President Obama has introduced some programs that are “rational” but are also not world-leading in their ambition. The best publicized portions of his energy saving plans have been higher fuel efficiency standards for trucks and cars but these are not world-beating. He has introduced some sizeable tax incentives for electric vehicles. He announced an initiative to increase energy efficiency in commercial buildings 20% by 2020 which is better than before but by no means a “stretch” goal. Strategically these initiatives have gotten buried in the news cycle as the President appears to want to show himself as “not a liberal” which the Right wing associates with energy efficiency and conservation.

Climate Bill Hangover or Ideology?

Many of the energy and environmental initiatives and policy direction of the first year of the Obama Administration were packed in the ACESA climate bill that barely passed by the House of Representatives but which in a modified version stalled in the Senate. The lack of a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate made the passage of the even less ambitious Senate bill impossible. At the time, the dysfunction of the US Senate was held responsible by many commentators for its failure, though some noted that Obama was not campaigning heavily for either bill. The seeming diffidence of Obama in these matters was in retrospect striking, though the standard of comparison in 2009 was the backwards-looking Bush Administration, so by contrast Obama has been praised as the “greenest” President to date.

Without this omnibus bill, Obama’s energy policy has been pieced together and in a manner that indicates that the Obama Administration does not prioritize sustainable energy and climate concerns if they at all conflict with an inside-the-Beltway political calculus. Luckily the 2009 one-time stimulus package contained greener energy initiatives which continue to yield some benefits, including the HSR funding as well as renewable energy loan guarantees mentioned above. However within the Obama political strategy, the optically “Left” appearance of ambitious climate and energy action seems to outweigh any upside from real benefits to either the American economy or the global environment of more aggressive policies. At best, the Obama Administration is “stealthily” green where it will not be noticed by his Republican opponents; Obama seems unwilling to fight about the environment with his opponents who deny the potential of human beings to do harm to the natural world.

The recent offering of coal leases in Wyoming indicates that the Administration is also solidly behind the fossil fuel industries and shows little concern for climate impacts. We see, at least in this first term of the Obama Administration an “ideology” of trying to offend as few people as possible, court Republicans and right-leaning independents, and in the process putting the United States further behind in green energy and climate.

Paling in International Comparison

While the Obama Administration appears “green” in comparison to the Bush Administration, in energy policy, the US lags most European countries and is actually in many respects has a much weaker climate and energy policy than energy- and coal-hungry China, if the relatively privileged geographical position of the US is considered. Unlike many European countries and China, the US is not resource constrained when it comes to renewable energy sources and could theoretically build multiple “Renewable Electron Economies” using copious wind and solar resources. A conservative German government has just committed to doubling the share of electricity generated from renewable sources by 2020 and replacing its nuclear power plants with renewable energy. Denmark is pledging to go 100% renewable by 2050. China, while it continues to pursue an “all of the above” strategy, has been extremely aggressive in pursuing renewable energy and high speed rail.

Not Confronting the Cheap Energy Contract

A fitting explanation for the failings of US energy policy over at least the last three decades is the continued rule of the Cheap Energy Contract, a label I invented three years ago for a common concept in American politics. A mostly North American social contract, the Cheap Energy Contract is an implicit and explicit commitment by lawmakers in the US and as well as the energy industry itself, that the price of energy must be as cheap as possible in the near term. An adherence to the Cheap Energy Contract means that adding an energy tax of almost any kind is considered to be political suicide as well as any actions that could be construed as raising energy prices viewed from the perspective of a future political campaign.

President Obama’s apparent unwillingness to confront our fossil fuel energy habits and, moreover his tendency to encourage those habits in the short and medium term, could be viewed as efforts on his part to immunize himself from accusations that he “raised the price of gas” which could lead to election day fallout. But Obama is not alone in his adherence to the Contract, a current obsession of leftward portions of the political spectrum currently is the role of speculators in the high price of gasoline at the moment. Bernie Sanders, a reliable voice on the Left for many issues, is very loud in his protests about the role of speculators in raising the price of gas, hurting his mostly rural constituents. In these discussions, the positive role of an ascending carbon or gasoline tax in weaning America off petroleum is not often mentioned. Obama in this regard is not exceptional but also not assuming a leadership role in energy at a critical period in our history.

Effective Energy Policy is a “Do or Die” Component for a Sustainable Future

While talk of “energy markets” is common, what is often overlooked is that these energy markets are in part artificial constructs, co-created by years and decades of energy and infrastructure policy by government. Individual private or sometimes public enterprises may discover or develop a certain energy resource but soon the interconnected nature of how energy is used and produced creates the need for government to create rules and/or provide infrastructure so that energy can be used to the extent and at a price that consumers and businesses demand, while keeping in check monopolistic and oligopolistic excesses via regulation. Even in market economies, there is more and less planning to be found in energy policy and energy infrastructure, depending on the country.

Against those who hold up the chimera of a completely “free” market, planning by governments is critical for a sound energy policy to emerge. A lot of this has to do with the fact that energy consumers, when they are using energy, could generally “care less” about how that energy is produced, unless they are participating in a large-scale national or international “mission” related to energy. If energy is treated as simply a unit of “utility” by the consumer, the sustainability or non-sustainability of the source of energy is ignored. While some of the products (motion, heat) and byproducts (pollutants, fire) of energy use are sensible by people, the energy itself cannot be sensed. Government policy is under most conceivable conditions the means via which a framework of meaning and measurement can be constructed around energy. Therefore we rely most on government policy to make distinctions between energy sources.

Energy Policy as a “Funnel” to the Future

Obama’s “all of the above” energy policy, keeps us beholden to the “care less” or “lazy’ reliance on whatever energy source is least expensive or convenient at one moment in time or another. If we continue to pursue energy opportunistically, like for instance, fully exploit the tar sands of Alberta, and fail to institute a significant and rising carbon tax, we will be unable to build the energy future, or at least others will end up building it and leaving us behind.

Rather than “go every which way” in our search for and use of energy, seeking out and consuming “joules’ in whatever form we may find them, government policy needs to focus energy users on sustainable options, functioning as a “funnel”. One might think of there being two forces in a policy funnel, positive and negative forces. A positive force “draws” people towards new sources via incentives or provision of sustainable alternatives. A negative force, the “sides” of a the funnel, redirects behavior away from harmful uses of energy, either in the form of a prohibition or a price placed on dirty energy. The ability to say “no” with sufficient political legitimacy is key to the creation of an effective energy policy, as is the provision of adequate positive choices that have low social and environmental external costs.

So far, though President Obama seems intellectually aware of many of the dimensions of the problem in some of his speeches, he has not fought for a “funnel-like” energy policy, instead reinforcing the status quo, out of what appears to be fear of his political opponents. The politically safe focus on “more innovation” avoids the issue of pushing for policies that deploys the solutions that we already have that can get us a long way to where we need to go. While this seems to be part of a larger political and economic worldview that unfortunately the President either believes or implicitly accepts as true, energy policy is I believe a critical component for Obama to become a transformational President. Even if he does not, from the point of view of character, want to be a transformational figure, the real challenges of our society require our leaders to step into this role anyway.

I realize that funnels are not the most attractive concept as applied to human behavior; I invite others to come up with better or more attractive ideas. I would still caution that one critical component of any effective energy policy or policy metaphor is the introduction of reasonable constraints on human energy-using behavior. The advocacy of these constraints will always provoke attacks from people operating under a quixotic vision of freedom that has no physical supports or characteristics. For us to maintain our real freedoms, we must refrain from using up all fossil fuels, starting very soon indeed.

In subsequent posts, I will outline what this policy “funnel” might look like, even though it may fall on deaf ears in Washington.

Energy Policy “Carrots and Sticks”: Bernard Chabot’s Profitability Index Method for Feed-in Tariffs July 19, 2010

Posted by Michael Hoexter in Energy Policy, Renewable Energy, Sustainable Thinking.2 comments

Often policymakers are “flying blind” with regard to how they will incentivize or disincentivize various market and other social activities via policy design. Part of this has to do with the complex network of stakeholders that are always involved in the design of policy as well as mismatches between the influence of one or two powerful incumbent stakeholders and the less powerful. Another factor is that policymakers often need to rely on a disorganized web of economic opinions about how the economy works and how policy works, over which they themselves do not have clear oversight.

Bernard Chabot, a mild-mannered renewable energy engineer from France with extensive business and policy experience, has designed a system that may very well make it easier for policymakers to design policies that work according to public intentions. Last week at the national offices of the Sierra Club, I was able to attend Chabot’s Workshop on Feed in Tariff design sponsored by the Kern-Kaweah Chapter of the Sierra Club, organized by the leading North American feed-in tariff advocate Paul Gipe. The workshop was attended mostly by feed-in tariff and renewable energy advocates from the western US. Besides over 25 years working in the field of renewable energy and energy efficiency, Chabot has consulted in the design of the Ontario and the French feed-in tariffs so brings to the workshop a good deal of authority with regard to the technical, policy, and business aspects.

Chabot bases his method on a much overlooked tool from corporate finance and business economics, the Profitability Index. The Profitability Index (PI) is a number that is arrived at by dividing the present value (PV) of an investment by the total capital cost of the investment (I). Chabot alters this slightly by using NPV in the numerator, which means Chabot’s PI uses 0 as the “break even point” like NPV rather than 1 like the traditional Profitability Index. As NPV is much more widely used than PV as a decision tool, Chabot’s alteration can be considered justified. What emerges are a range of values that usually range between 1 and -1. Chabot explains how PI can be used as a universal value for understanding the profitability of various economic and even more broadly social activities and makes an argument that businesses and financiers more generally should use PI over other business measures of return on investment. Chabot has some fairly convincing arguments that using the more popular internal rate of return (IRR) statistic leads to some misleading results and unforeseen variations in how at least renewable energy policy turns out for different market actors.

In terms of policy “carrots and sticks”, Chabot observes that policymakers should make highly desirable activities more profitable than less desirable activities by using the profitability index as a guide. In manufacturing, a profitability index of 0.3 is minimal but in project development or construction with no R&D costs, such a PI would be highly incentivizing. On the other hand, harmful activities should be made less profitable by the imposition of taxes or the removal of tax subsidies, pushing their profitability towards zero or below.

Turning to feed-in tariffs, Chabot uses PI as the basis for developing incentive policies which enable policymakers to keep profitability levels at acceptable but not excessive levels for project developers and facility owners. As above, given the relatively low risk involved in a well-designed FiT, Chabot believes the PI should range between 0.1 and 0.3 for both simple “flat” FiTs and Advanced Renewable Tariffs. Chabot believes some of the policy missteps in FiT design in certain areas could have been avoided if policymakers had used the PI method.

While FiTs are considered by almost all observers of the renewable energy scene to be the policy of choice, some simple FiTs have run into problems with either excessive profitability and an overheated market, which has attracted disproportionate attention by opponents of FiTs, or with insufficient profitability for certain types of projects. Chabot proposes the Advanced Renewable Tariff (ART) as means for designing tariffs for wind or for regions with wide variability in the strength of renewable resources. A single flat tariff for solar in California for instance, would make projects in southern and eastern California extremely profitable relative to projects along the foggy coast. Similar variation can be found in many US states. Wind resources vary widely by location as well. The two-tier ART consists of two tariff levels with an initial higher tariff followed after a period of years by a lower tariff; those areas with a lower resource strength will continue at the higher tariff level longer in order to enable most reasonably well designed projects in areas with adequate resource to achieve minimal profitability. ARTs can be designed any number of ways but Chabot believes that the policy should reward utilization of the best resource areas with higher but not excessive profitability yet not overbuild solar or wind in areas with poorer resource base.

Chabot feels that ARTs are a critical instrument for a vast country like the US with multiple climate zones to be able to create policies that will spur investment in renewable energy. Similarly countries like Italy, France and Spain with multiple climatic zones would benefit from ARTs.

In any case, I highly recommend that policymakers who are considering any number of different policy instruments that depend on incentivizing or disincentivizing various economic activities consult with Chabot and learn about his method. While I have only experienced his one-day workshop on pricing feed-in tariffs, Chabot says that his longer workshop deals with energy efficiency as well, which similarly involves cash flows and is amenable to the profitability index. His resume and information can be found here.

Book Announcement From Danny Harvey: Energy and the New Reality Vols. 1&2 June 20, 2010

Posted by Michael Hoexter in Climate Policy, Efficiency/Conservation, Green Building, Renewable Energy, Sustainable Thinking.add a comment

I recently became acquainted with the work of Danny Harvey, Prof. of Geography and a climate scientist at U. Toronto. Over the last few years, Danny has been putting together a large-scale energy plan that might be called a Renewable Electron Economy, to which a portion of this website is devoted. I believe Danny’s work is invaluable because he presents a great deal of detail about a wide range of technological solutions and also links these to climate scenarios. His website has a series of extensive powerpoint files which provide you with a great overview of most of the relevant issues in the climate and energy debate with a strong technical and scientific grounding. The materials on his website are available for educational use and with permission for other uses. Upon my request, he has sent the announcement of his new two volume book “Energy and the New Reality” published by Earthscan to which the powerpoint slides are linked. The first volume concerns reducing energy demand through energy efficiency and the second volume with carbon-free sources of energy. I highly recommend that anyone with even a mild interest in climate and energy issues take a look at Danny’s work.

Two new books by Danny Harvey (Dept of Geography, University of Toronto),

Energy and the New Reality, Volume 1: Energy Efficiency and the Demand for Energy Services (Earthscan, UK, 614 pages)

and

Energy and the New Reality, Volume 2: Carbon-Free Energy Supply (Earthscan, UK, 576 pages),

comprehensively and critically assess what it would take to stabilize atmospheric CO2 concentration at no greater than 450 ppmv, and can be purchased through links on my website (given in the email signature).

Some of the key conclusions from these books are that

• it is still technically and economically feasible to cap CO2 at no more than 450 ppmv without replacing existing nuclear power capacity as it retires and without resorting to carbon capture and storage (CCS), although the latter could be – in combination with bioenergy – part of a strategy to more rapidly draw down atmospheric CO2 from its peak than would otherwise occur;

• nuclear energy and CCS would, at best, be too little too late, whereas reliable C-free energy systems can be built up on the required time frame and likely at no greater cost than nuclear energy or CCS; and

• we will almost certainly have to abandon our insistence on continuous economic growth above all else if we are to have a reasonable chance of avoiding eventual global ecological and social catastrophe.

Complimenting these books are powerpoint presentations (with figures, summary tables, and explanatory notes) for each chapter (a total of 1899 slides) that can be obtained either through the publisher’s website (www.earthscan.co.uk/?tabid=102427) or the author’s website (faculty.geog.utoronto.ca/Harvey/Harvey/index.htm). These powerpoint files would be a valuable resource even without purchasing the books, but if slides from them are used in any public presentations, the source of the figures (whether the author of the books or the original sources given with the figures) should be acknowledged.

Also posted on my author’s website are (1) pdfs of the table of contents and chapter highlights for each book, (2) pdfs of the summary (policy) chapters from each book, (3) the package of Excel files used to generate all of the energy demand and supply scenarios presented in the two books, (4) an Excel-based building stock turnover and energy demand model, (5) the FORTRAN code and input files that are also used in one step in generating the energy demand scenarios, and (6) the flyer for the books and a link to the publisher’s website for those who wish to purchase the books (for professors, complimentary copies can be obtained if the books are adopted as course textbooks).

The author’s website also contains an Excel package on climate and carbon-cycle modeling that will be part of the online material associated with the author’s chapter in the forthcoming book, “Environmental Modelling: Finding Simplicity in Complexity, 2nd Edition” (Wiley-Blackwell, John Wainwright and Mark Mulligan, eds.). CO2 emission output from the Energy Excel package can be conveniently pasted into the second Excel package and used to generate scenarios of global mean temperature change for a variety of easily-changed assumptions concerning climate sensitivity and the strength of various climate-carbon cycle and internal carbon cycle feedbacks.

FURTHER DETAILS ON THE EXCEL FILES AND FORTRAN CODE:

The idea behind posting the Excel files and FORTRAN code is to permit those who are so interested to generate their own scenarios with their own input assumptions concerning population, GDP per person, activity levels per person, and physical energy intensities for various energy end uses in 10 different geopolitical regions, as well as to generate scenarios for energy supply from various C-free energy sources. Outputs from these files include global demand for fuels and electricity, annual material and energy inputs required to build a new energy infrastructure, land requirements for bioenergy, and annual and cumulative CO2 emissions to 2100 (the CO2 emissions in turn were used as inputs to a coupled climate-carbon cycle model to produce the scenarios of global mean warming and ocean acidification that are given in ENR Volume 2). The FORTRAN code applies a building stock turnover model to 2 different energy sources (fuels and electricity) in two different building sectors (residential and commercial) in the 10 geopolitical regions, and uses as input the growth in regional building floor area as generated from the Excel demand scenarios, along with a variety of other inputs.

The stock turnover model has also been implemented in Excel for one generic fuel, building type and region for those who wish to adjust the inputs to a particular region and building type of interest so as to explore the impact of alternative assumptions concerning growth in total floor area, rates of building renovation and replacement, and the change over time in the total energy intensity (annual energy use per unit floor area) of new buildings and of newly-renovated buildings.

The climate-carbon cycle Excel package (subsequently referred to as the CCC package) has three parts. The first part contains a number of worksheets that explain the physics of climate change and the development and properties of simple climate and carbon cycle model components. The second part of the CCC package contains a highly-simplified representation of the energy demand and supply framework used in my two energy books. These give scenarios of global fossil fuel emissions of CO2. CCC package also has worksheets that give land use emissions of CO2 and total anthropogenic emissions of CH4, N2O and halocarbons (all subject to alteration). The impacts (radiative forcings) of tropospheric ozone and aerosols are computed in a manner that is roughly consistent with the fossil fuel and land use CO2 emissions. The third part of the CCC package contains a coupled climate-carbon cycle model (built from the components illustrated in Part 1) that is driven by the outputs from Part 2. The climate sensitivity and a number of carbon-cycle and climate-carbon cycle feedbacks can be specified (including the possibility of eventually catastrophic releases of CO2 and methane from permafrost regions beginning slowly at some user-specified threshold temperature change). The climate-carbon cycle model in the CCC package can be driven either with the fossil fuel CO2 emissions that are generated from Part 2 of the package, or with the CO2 emissions that are produced from the Excel package for the two energy books (these emissions can be pasted into the CCC package). In this way, those who are so interested can explore the range of possible impacts on climatic change (given uncertainty in climate sensitivity and climate-carbon cycle feedbacks) resulting from very specific assumptions concerning future population, economic growth, activity levels and physical energy intensities at the regional level, and in the rate of deployment of C-free energy supplies at the global scale.

The Deepwater Oil Spill Exposes a Persistent Failure to Plan and Failure to Lead May 16, 2010

Posted by Michael Hoexter in Climate Policy, Efficiency/Conservation, Energy Policy, Green Transport, Renewable Energy.Tags: Climate Policy, Electric Vehicles, Energy Policy, Oil Independence, Oil Spill, rail electrification

5 comments

The 1969 Santa Barbara Oil Spill catalyzed the environmental movement in the US and inspired some important legislation but did not lead policymakers to take the next step and start the long process of weaning the US from its oil dependency (Photo: Unknown)

President Obama is facing with the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon, a “local” disaster that exposes a deeper, endemic crisis in US energy policy and the US economy as a whole. As he has been in office for still just 16 months, Obama does not bear primary responsibility for this ongoing crisis but he has only recently, a couple weeks after the accident, publicly hinted at the “elephant in the room”: the obvious connection between the undersea oil volcano and our equally obvious need to transition from using oil as our primary transport fuel. Simple reference to the Kerry-Lieberman climate bill that encourages more offshore drilling does not constitute an answer to our oil dependence.

Unfortunately public rhetoric and policy discussions that hinge on the notion of a dependence on “foreign” oil play the role of a “shortstop” in keeping the discussion from going to the heart of the problem. The idea that oil produced on American shores will somehow differentially serve American consumers overlooks the international nature of the oil business with total offshore oil reserves destined never to make much of a difference in the overall price and availability of oil. Estimates put the total reserves of offshore oil in US waters at 18 billion barrels conventionally recoverable and an additional 58 billion barrels “technically recoverable”. While this oil, if extracted, would just be sold on the world market, it equals the equivalent of 11 years of consumption for the US at our current oil consumption rate of 8 billion barrels/year. Subtracting the huge costs of oil spill cleanups and damage, most of the economic benefit of offshore drilling would accrue to oil companies and secondarily to state and federal governments in harvesting royalties, however the latter are going to be left “holding the bag” for the really, really big costs.

To ground this discussion in reality for just a moment, the 2009 US DOE Transportation Energy Data Book attributes to the US 2% of the world’s oil reserves, 8% of production, and 24% of consumption while the rest of the non-OPEC world comes out just a little better at 29%, 48% and 67% respectively. Conventional natural gas is not a much more promising energy source for the future with the US having 3% of the reserves, 18% of the production, and 21 % of the consumption. In the US, transportation accounts for 70% of all petroleum use and 24% for industrial uses. Consumption of petroleum for transportation in the US is 84% for road transportation with around 65% for cars and light trucks and 18% for medium and heavy trucks. Airplanes use 9%, shipping 4.2%, and rail 2.0%. Even if we consumed petroleum and natural gas in proportion to worldwide production, there are credible predictions that we are somewhere in the neighborhood of the worldwide peak in production whether today or in a decade’s time. Even if there were two more decades until the peak and we looked away from oil’s climate and local pollution impacts, would it be justified for our generation to run through this exhaustible resource?

The ballooning US trade deficits are attributable in the last decade approximately 55-60% to outgoing payments for petroleum imports but with the 2008 price spike, oil’s proportion climbed to 65%. With oil prices once again ascending the petroleum related component of the US trade deficit will continue to climb. With the last US trade surplus in 1973, the total US trade deficit has since 2003 stayed in the range $500B to 800B per year.

Turning back to politics, the President, whether by his own inclination or badly counseled by his advisors, has since taking office had a tendency to let the issues be defined for him rather than shaping policy with original view of his own. He has approached health care, financial reform, and climate and energy as though there was some pre-formed wisdom which he simply needs to allude to or tap into in order for the American people and Congress to understand. Erring on the side of being too laid back, perhaps partaking of the Spirit of Aloha, has not always served him well: to get health care across the line he had to shed the “cool customer” image to actually win the votes in Congress.

The apparent rationale for his laid-back approach to issues, so commentators say, comes from overlearning what is considered to be a mistake of the early Clinton White House. Clinton’s hands-on approach to policy is supposed to have alienated Congress and doomed Clinton’s health care efforts. Obama has taken the opposite tack and can claim at least passage of a health care bill, though it is not clear yet how positive an achievement this will be considered when it actually takes effect.

What is missing so far in the Obama Presidency is the President taking the role of educating and perhaps changing the public’s views on important issues, which have been heavily colored by a very strong and organized counter-reform messaging machine. The President has shied away from using the “bully pulpit” and allows Congress, which is considered by the public at the moment to be corrupt and untrustworthy, to shape the terms of the debate.

With the approach to a climate and energy bill this year, post-health care, the President opened up with a tactic rather than with a strategic plan for energy. His announcement in March that he would lift the ban on offshore drilling in parts of the Gulf and the East Coast was a means of gaining support from Republicans for the ever more amorphous climate and energy package which is currently in the Senate. Meanwhile, with so many issues and concerns, it is safe to say that energy is not top-most on most people’s minds in the Great Recession.

But the President has so far treated this as a case of another industrial accident for which liability can be assigned to the owner or commissioner of the oil rig, BP. President Obama has not even advanced to the rhetorical level of George Bush’s 2006 State of Union where Bush declared America “Addicted to Oil”, despite Bush, in action, being responsible for gutting the regulatory agencies that may have prevented the spill. While nominally a more “liberal” President and not from the oil patch, Obama has not presented a tangible vision of a post-oil society and, in combination with his preferred policies and speeches, the public is left mired in the oil-dependent present.

Discussions about who is to blame, who will pay, and what can be done in the Gulf to recover from the spill are important but are ultimately distractions from the most important question:

What will the US do to wean itself from its oil dependency?

In media accounts, the effort to make this a conventional tale of corporate or regulatory malfeasance is becoming the favorite of supposedly hard-hitting television journalists. Yet these interviewers avoid looking into the frightening “maw” of our economy’s fatal dependence on oil. The President is also looking away, focused as he is on technical and regulatory “fixes” for the offshore drilling disaster.

The upcoming climate bill in the Senate is being sold as an effort to reduce our dependency on oil and other dirty fuels but it contains few aggressive provisions to get us there. The just released details of the bill, indicate that it’s mild cap and dividend provisions may slightly raise oil prices (starting in the area of $.10-$.20/gallon and increasing by 3-5% over inflation per year). And offshore drilling provisions are in the current draft, offered now as an opt-out for states that wish to keep the ban in place. As a whole, the bill postpones until the 2020’s any serious moves to cut emissions and focuses on the implementation of coal carbon capture and storage rather than more promising renewable technologies and grid enhancements. Ironically, Senator Kerry has mentioned on TV, as if this were a sign of his seriousness, that he had been working with the oil industry on this bill.

If we assume the best intentions of the President and the Congressional leadership, one single legislative session or bill cannot undo 30 years of negligence and foolish disregard in the area of energy. Whatever his ultimate goals and political commitments as President, Obama, if he endeavored to “do the right thing”, would have a number of hurdles (described below) to overcome. However right now, he, his Administration and his Congressional allies are managing just a few cosmetic moves in the direction of change. On the issue of oil use and oil dependence, the bill and the Administration’s efforts are weak.

I am proposing here a stronger response that deals directly with America’s oil dependency.

A Strategic Energy Plan for Oil-Independence and Carbon Mitigation

A serious effort to get off oil will involve an equal emphasis on battery electric and grid-tied or grid-optional large vehicles like this trolleybus. The de-electrification of public transportation, while greeted by some as progress, now appears to have been a big mistake. (Photo: Adrian Corcoran)

The only solution to our oil dependency and the inevitable disasters that come from a mad rush to extract as much oil as possible from the earth is to create a strategic national energy plan that addresses both our oil dependence and our climate concerns. A plan is required because changes in the transportation and energy system involve the coordination and arrangement in a sequence of certain key activities and infrastructure changes, for which market mechanisms, the current “default” preference for policymakers of both Left and Right, are ill-equipped. Such a plan would also be the occasion for leaders of government to show and exercise leadership rather than look around for a lucky break or well-meaning private actors and companies to step into the breach. Turning to planning is unfortunately now in America a politically fraught move but there is simply no alternative, if we want to have a sustainable economy, whether in the narrow economic sense or the broader ecological sense.

A growing chorus of corporate leaders and former government officials is calling for an electrified, oil-independent transportation system for national defense reasons as well as environmental ones. Recently Bill Ford, chairman of Ford Motor Company made the connection between national security and oil, indicating that Ford’s product roadmap will focus on electric drive vehicles in the future. James Woolsey, former CIA chief under Clinton, has been a long-time advocate of electrification for reasons of national defense.

Other nations are rapidly moving away from oil through plan-based efforts by governments in coordination with the private sector, even as almost every other country is starting from a position of less oil-dependence than the US. The Chinese leadership, as is well-known, is very concerned about the effects of oil shortages and prices on China’s economic development. China is in the process of building an extensive high-speed rail network (to Europe too)and is as well working on developing a lead in the area of battery powered vehicles. President Obama mentioned in a recent speech China’s ambitious rail program as an analogue to his efforts in the US but I believe he knows that there is no comparison between the scale of their efforts and our much modest ones. Japan and Switzerland have almost entirely electrified rail networks and France has the goal of electrifying its entire rail network by 2025. Russia, despite its plentiful oil reserves, has electrified the Trans-Siberian and Murmansk lines of its railways in the last 10 years. Denmark, Japan, France, and Israel all are executing plans to build widespread electric vehicle charge and battery-swap infrastructure. By contrast, US freight and passenger transportation in all modes is almost totally dependent upon oil, leaving the US vulnerable to political and geological disruptions of supply and price spikes (see Alan Drake’s proposal for a comprehensive electrified train system for the US).

Two Pronged Strategy: Efficient Use and Oil-Independent Infrastructure

There are two prongs to getting off oil which also share a common path. One prong is increasing the efficiency of oil use in the US via increasing the person or freight miles traveled per unit petroleum consumed. The other prong is building an oil-independent transport infrastructure and oil-independent vehicles. Investment in routes on the path common to both should be favored over those that commit us interminably to oil.

The dream of a quick-fix, a “drop-in” technological solution that will simply replace oil has proved to be elusive and has so far found little basis in the science of energy. So the proposed solution has a number of parts and involves tradeoffs and some large initial costs. However, the invitation is there to any readers to find a better, presently available solution and publicize it.

Efficient Use:

- Levying a gas tax or price stabilization tax that insures that drivers can plan on a minimum gas price going forward on an ascending schedule. Instead or in addition, a carbon tax or fee would disincentivize coal use as well, though might be supplemented by a gas tax to reduce gas use. (the Kerry Lieberman bill’s cap and dividend provisions will raise gasoline prices imperceptibly in the first few years).

- Enable full use of existing passenger rail and bus transportation infrastructure via adequate funding to increase schedules, keep current fare levels. Determine via market surveys and statistics optimal service levels for each route.

- Encourage shared ride and shared vehicle programs and services using Internet and mobile phone resources to coordinate and develop ride-sharing social networks

- Mandating idle-stop systems (a.k.a. “mild hybrid”) on all new trucks and cars as of 2013. Comprehensive idling reduction program at all truck stops, including incentivizing “shore power” electric hookups and retrofit kits. Mandate Cold ironing facilities at all shipping berths by 2015.

- Incentivize Transit Oriented Development via federal incentives for zoning changes at the local government level and developer and homeowner tax incentives.

While focusing on efficient use alone seems “pragmatic”, it actually does not have nearly the appeal and long-term economic stimulative effect of building an infrastructure that moves passenger/driver miles and freight ton-miles off of oil permanently. To focus on efficient use without building for the long-term is an incomplete strategy.

Oil-Independent, Carbon-Independent Infrastructure:

See Drake et. al. for a slightly different more detailed proposal

- Double or multi-tracking the US rail system on all but low traffic lines enabling consistent speeds of 110 mph on non-high speed lines for freight and passenger trains.

- Stepwise electrification of rail infrastructure to 100% electric traction.

- Building on an accelerated basis dedicated high speed rail lines per the US HSR Association’s recommendation: http://www.ushsr.com/hsrnetwork.html

- Electrification of 80% of government vehicle fleets using a variety of battery charging technologies including trickle charge, rapid-charge and battery exchange technologies.

- Extended tax incentives for corporate vehicle fleet conversion to battery power or for plug-in hybrids.

- Rapid build-out of a super-grid supportive of renewable energy development throughout the US.

- A robust regime of incentives for renewable energy development (advanced feed in tariffs based on cost recovery plus reasonable profit with descending incentives for projects in later years).

- Electrification of high traffic bus routes via either trolleybuses or streetcars.

- Build out of light rail and regional rail networks to interconnect high and medium density cities and suburbs.

- Corporate tax credits for build-out of tele-presence (e.g. Cisco’s product here) technologies and to encourage tele-commuting and tele-meeting

While technologies could evolve in the future that might alter the relative proportions in the above plan, these policy proposals and programs rely on technologies that are available today, some of them with a track-record of over a century. However, the goal of getting off oil, let alone fossil fuels has not been a priority of US industrial development and government policy, so our rail and transport networks have remained dependent on the happenstance of oil extraction and the oil markets.

Substantial and Insubstantial Hurdles that Delay Us

If our country does not first slide into a state of permanent second or third-class status, it is inevitable that we in the US will move to a post-oil, post-carbon transport system incorporating most of the largely electric-drive technologies listed above. However this should not lull our current leadership into complacency or half-measures, because sliding into a state of decay and dependency is a distinct possibility. Will Obama be the President to lead us there, as Eisenhower was the President who built the Interstates? Or will he be the President who excited hope, talked a good game but gave too much discretion to fossil fuel interests? We can be the last nation in the world to wean ourselves off oil, massively in debt, and always be in the position of borrowing know-how from others or we can start to move “on our own power” towards a position of leadership in this area.

The current Senate climate bill sees most of what is proposed above as distant pipe dreams rather than near future realities. Most of the electric vehicle provisions in it are termed “pilot programs” with greater favor shown to natural gas vehicles and mild oversight for unconventional natural gas extraction. Public transportation and rails are given little or no mention.

Leadership will be required to push ahead to the solutions based on what is already known about the physics and technology of transport and energy, instead of stopping at the half-way measures or the dead-end technologies that depend on fossil fuels. True leadership involves anticipating and overcoming hurdles. I have listed below the main hurdles which present themselves to whomever, I hope President Obama, decides to place the American economy on a sustainable energy basis.

Hurdle #1: Market Idealization (Market Fundamentalism) Vs. Planning

One of the greatest hurdles is the ongoing influence of market idealization (or “market fundamentalism“) in Washington in general, on both sides of the aisle in Congress and in the White House. In the era of market idealization over the last 30 years, planning, especially government planning, got a bad name as markets were supposed to constitute all of economic life as well as being perfect and complete economic institutions. Through his sojourn at the University of Chicago, one of the centers of market idealization, President Obama was exposed to an environment that celebrated a view of markets as self-sufficient, self-regulating institutions which perhaps continues to color his view of planning and government’s role.

The use of “cap” legislation, carbon pricing, or emissions targets does not substitute for planning because such unspecified “plans” to achieve quantities of emissions reductions cannot substitute for the sequence of timed and specified actions that constitute a plan. Emissions caps or targets suggest that the market will find its way without planning. In some areas this works better than planning but in transportation and energy infrastructure, not so much.

Some major problems with markets are that they don’t price in future risks or distant future rewards very well in many sectors, including energy and transport, and, when unregulated, tend to focus market participants on their most immediate concerns. Markets also do not produce all the conditions for their own survival and continued profitability. Governments have historically stepped in to provide people and markets with structure for transactions that threaten to undermine trust between market actors. Additionally, governments of most nations with complex economies provide public goods like infrastructure that enable longer term social and economic goals of both private and public actors to be achieved. While market-like institutions can be imposed upon the “natural” monopolies of the electricity and the rail businesses, these market reforms do not generally orient these businesses to rapidly change their infrastructure but rather focus them on squeezing value out of existing assets.

Planning can originate from private and non-profit actors as well as from government though this does not release governments from the duty to initiate or help structure plans that effect diverse sets of stakeholders. The Desertec Initiative is an example of a large-scale international energy plan that has originated in the private and non-profit sectors. The Desertec Foundation and the Desertec Industrial Initiative (DII) are working on building a renewable energy supergrid that spans Europe, North Africa and the Middle East in order to provide renewable electrical power to the area, balancing wind and solar resources across the region. Munich Re, a large re-insurance company based in Germany, concerned about environmental and climate risk in the future and along with a consortium of electrical utilities and technology companies, including Siemens, ABB, Abengoa, MAN Solar Millennium has created the DII. Whether the impulse to plan has come from the private sector or from government, government needs to be involved in making sure that large scale energy and transportation plans serve national interests and are executed and financed in a transparent and fair manner.

As market idealization has been also a particularly fervent form of anti-Communism, government involvement in planning has been associated in the minds of US politicians and sections of the public over the past 30 years with centrally-planned Communist economies. Due to these still largely unchallenged views of market idealists, politicians making the argument for planning will need to run the political gauntlet of being accused of being a Communist (or, as is common in the precincts of the Tea Party and Fox News, a fascist). Unfortunately, academic economists too have also been lax in making the case for government planning beyond Left-Right ideology. Republicans and Democratic Presidents and other government officials between 1940 and 1980 did not generally have to justify their use of planning but since 1980, planners and planning advocates have needed to keep a low profile.

So presenting a full-on Oil-Independence Plan from the side of government would present the President with either having to make a two-stage argument (first for a role for planning and then for the plan) or to compress the two together in one artful package. The latter is not inconceivable but, our President, so far, has shown more interest in pointing out how much he has in common with the Republican Party that has been almost completely captured by market idealists.

On the other hand, almost everybody in contemporary American politics is for energy independence and national defense. It is not a stretch to imagine our centrist to right-leaning Democratic President reaching across the aisle to push for a “Oil Independence Transportation Plan”. This would require preparation, research and political leadership by the President, the Administration and Congress but is eminently do-able. Thus a brilliant and principled politician, maybe even our current President, could present this plan as a combined act of patriotism and long-term economic good sense.

Hurdle #2: Deficit Worries and Hysteria

Given that we are in an economic downturn and tax revenues will not be able to be boosted substantially, a post-oil transport infrastructure built in a timely manner will probably involve deficit spending. Some parts of this system can be built and financed privately and paid back via user fees while others will have the status of public goods, like roads, that will need to paid for via taxes and or potentially inflationary deficit spending, i.e. printing money.

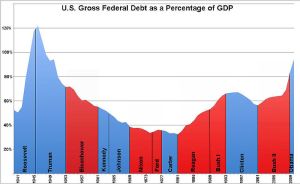

We have been facing a rise in public debt and budget deficits over the course of the Bush administration and the first part of the Obama Administration. The current level of the public debt stands at approximately 60% of its maximum in relationship to GDP at the end of WWII (108%). Misinformed politicians, pundits, and financiers take this as an occasion to stir hysteria that is stoked by a combination of fabrications and partial truths about the potential impact of budget deficits on the American economy. Economists, such as Paul Krugman, Dean Baker and Joe Stiglitz, who have studied economic history and effects of deficit spending on jumpstarting the economy, have attempted to correct these misguided views of deficit spending in the context of a severe economic downturn.

This graph of the "gross" and not the usually cited public debt (now at 67%) indicates that excluding the first year of the Obama Administration the last four Democratic Presidents reduced the gross federal debt while the last four Republican Presidents increased it relative to GDP. In general, economic depressions and wars tend to increase the federal budget deficit.

Deficit hysteria seems to have a strong political component to it, as these fears remained largely dormant in the Republican Administrations that have run up large debts in the past. As a preventative, those who are opposed to a strong government role in the domestic economy (though generally not to military adventures) have attempted to intimidate the President and others by warning of runaway budget deficits. There are now some more severe budget problems in other countries (Greece for instance) and the differences between the US situation and these countries are played down to intimidate those who would want to spend deficits on building US domestic economic growth.

While those who stir deficit hysteria tend to be closed-lipped about their large-scale political and economic agenda, they generally are opponents of all government-provided social services and government-led economic initiatives preferring to reserve these functions for private enterprise. Deficit hysteria implies the idealization of markets, though is a more sophisticated variety that acknowledges that there is “some” role for government, only to minimize that role in every proposal, due to fear of budget deficits. Unfortunately President Obama has some vulnerability to deficit hysteria, in that he has not come out vigorously in defense of government’s role in the domestic economy, preferring instead to adopt an attitude of compromise and conciliation with people who talk as if there is no legitimate role for government social programs or in the domestic economy.

While budget deficits need to be monitored closely, the US has luckily somewhat more flexibility than many other countries to engage in deficit spending. A very strong case can be made that deficit spending to help finance a post-oil transportation infrastructure is a very good use of public funds and also shows nations that hold our debt that we are spending in ways that will improve our overall competitiveness and resilience as a nation. Deficit spending in this way actually works to reduce our trade deficit which is in most years larger than our budget deficit and largely attributable to oil imports.

Hurdle #3: Balancing the Interests of Stakeholders, Mix of Private and Public Enterprise

The French SNCF is a public benefit corporation that runs and owns the French trains and stations. In order to open up the rails to competition the rails and rights of way are owned by another government-owned company, the RFF, enabling, theoretically, private train companies to compete with SNCF on the same tracks. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

An Oil- and Carbon-Independence Plan will require the participation of a number of stakeholders some of whom will be less than enthusiastic participants in this ambitious effort. The railways in the US are ambivalent about the ambitious plans of advocates for either high-speed rail or electrification. Like other large infrastructure-dependent businesses, these usually risk-averse corporations make money by squeezing value out of their existing infrastructure and sticking to decades-long incremental capital investment strategies. Additionally, and ironically, railways, our cleanest and most efficient means of transporting freight even with diesel traction, haul the dirtiest fuel, coal, to power plants of the large coal-burning utilities; the largest source of revenue for railways is coal transport accounting for 21% of 2007 revenue with intermodal (container) being the fastest growing segment.

Left to themselves, the US freight railways would not be able to undertake nor necessarily see it in their short or medium-term interest to electrify their railroads nor embark on a massive program of track build-out. The railways are in favor of tax incentives to help them continue capital improvements but these alone will probably be not enough to double and triple track mileage. The railways own their own rights of way and are currently entirely self-funding and compete largely on price and capacity with other freight modalities. In order for massive public investment to be possible, the railways would have to develop an entirely different relationship with the federal government.

If they were intent on executing a Post-Oil transport plan, policymakers would need to lead the railways into a new relationship or perhaps buy some of them out, in part or in full. The massive level of public investment required to enable the railways to carry triple the freight plus 20 to 30 times the passenger volume would transform their capital base with largely public funds or public guarantees to be able to undertake the risk. Such action would require a combination of vision, leadership and negotiation skills from the side of government.

As diesel locomotion (actually diesel-electric) is still a very efficient method of hauling freight and passengers relative to other modes of transportation, the transition to an Oil-Independent infrastructure could be achieved in two stages: first railway track build-outs that are electricity-ready and then the electrification of those railroads as a separate project.

An alternate route towards oil-independent transport is possible that “deals in” the trucking industry but requires the adaptation of several existing technologies and an alteration to the interstate system: Using hybrid dual-mode trolley long-distance trucks on dedicated lanes of the interstate that also have a backup generator or battery pack that enable easy on and off and grid-detached travel. There are no technological breakthroughs required to do this but it needs the backing of a government or government-funded research program that seriously studies electrification of lanes of interstates and the high speed attachment and detachment of trolley poles or pantographs to overhead lines.